“[…+THE BUILDINGS THEY ARE SLEEPING NOW]”

LOCATION

TAS

paredarerme Cranbrook & Swansea

Who are we?

We are creative collaborators who launch our architecture and dance from within DEEPROOM, a processed-based 30-year active ‘archive’ formerly based in Perth, Western Australia and now based in Hobart, Tasmania. Our lead creatives are Paul Wakelam Architect and Felicity Bott of Great Southern Dance. We work with many other exceptional and interdisciplinary artists. Our offerings to the Biennale Architettura 2023 are the Site Geist I and Site Geist II tactics. Via these works, we invite viewers to engage somatically and imaginatively with moving and still images of humans dancing within ruins of the machinery of colonisation.

Site Geist II

The visual language and conceptual articulations of this tactic resonate strongly with the Biennale’s overall themes. Although not directly involved in the creation of buildings, Site Geist II offers I adopts a relational approach, working with buildings in Cranbrook and Swansea, Tasmania.

Paul:

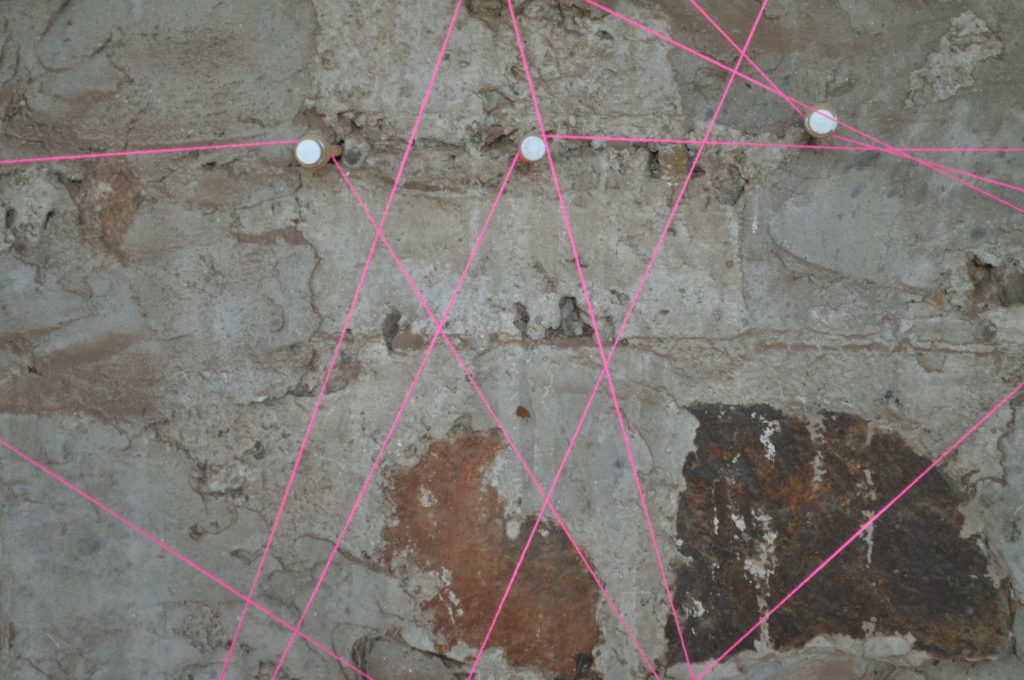

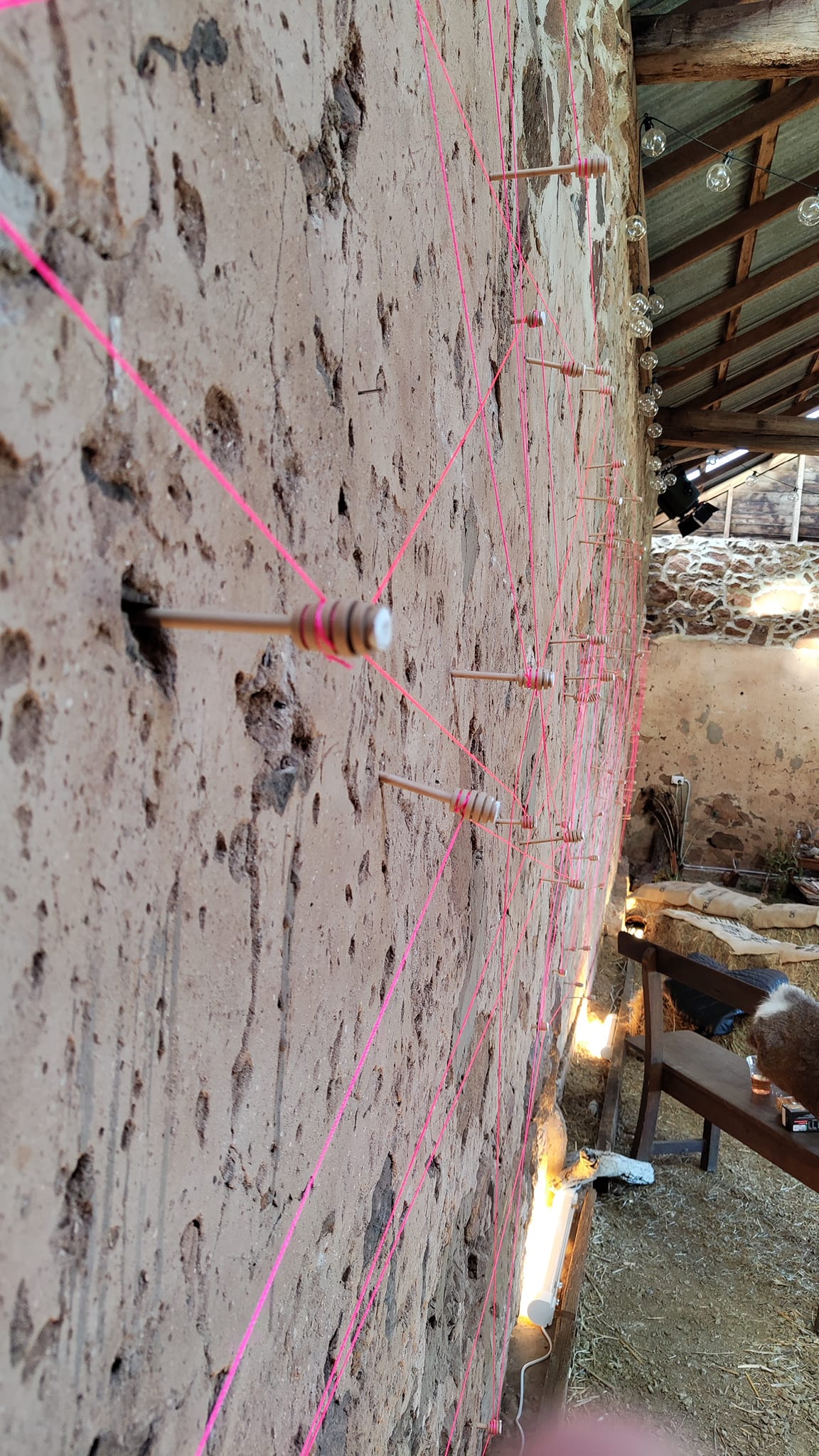

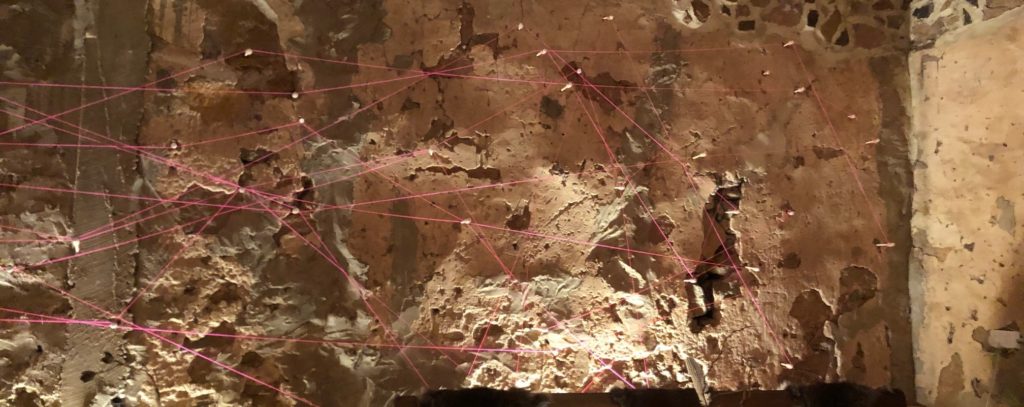

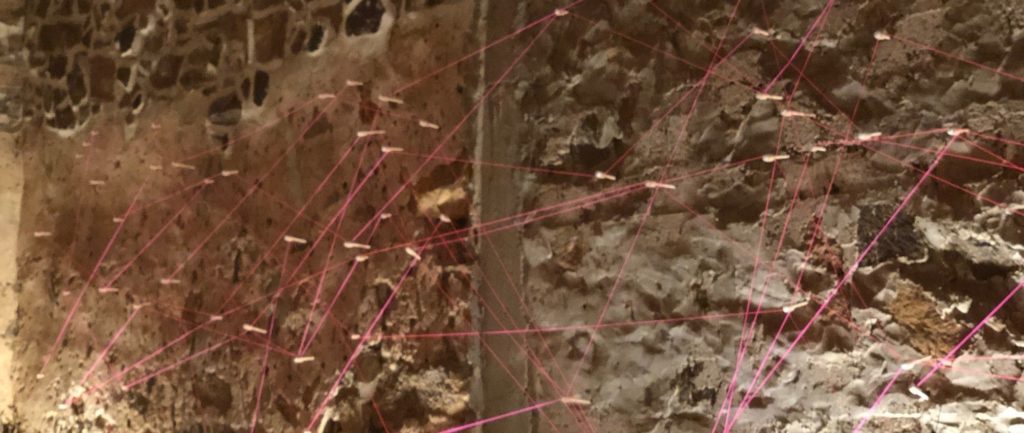

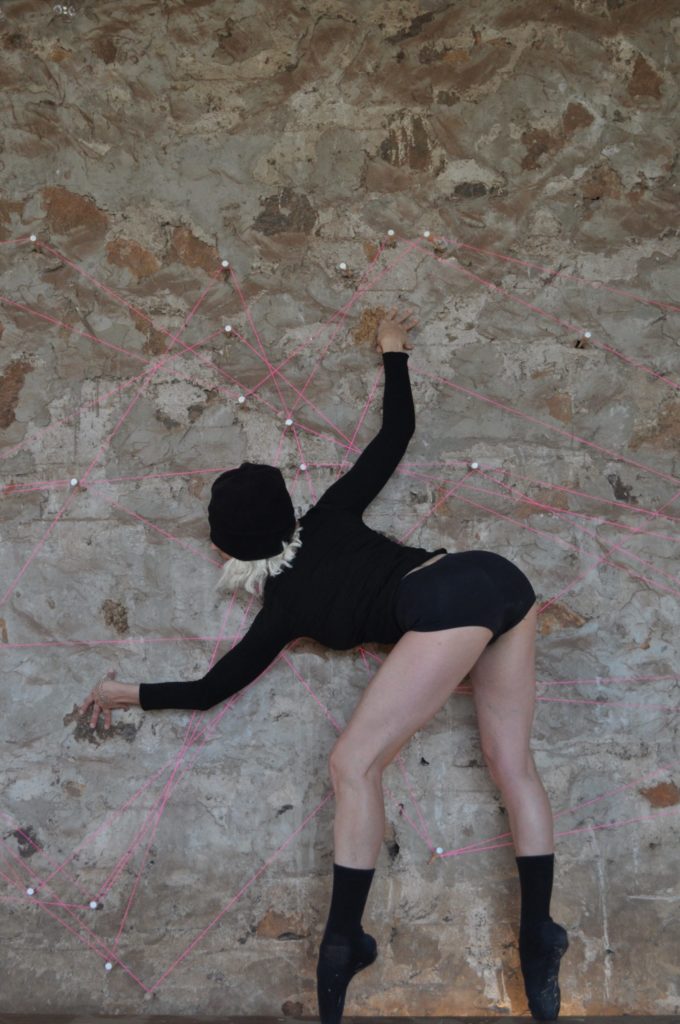

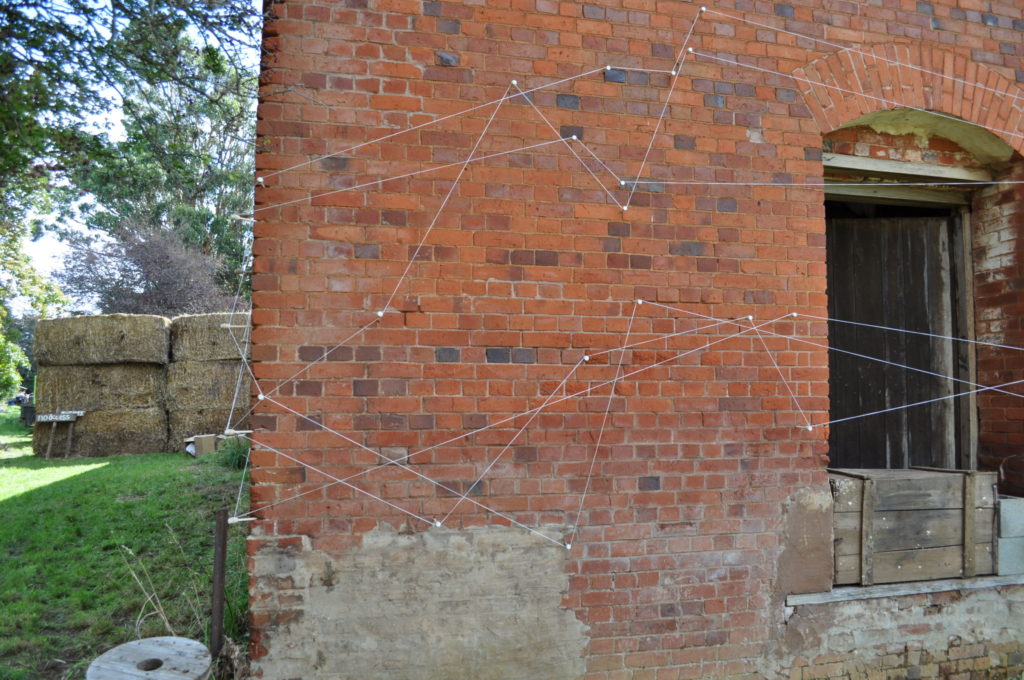

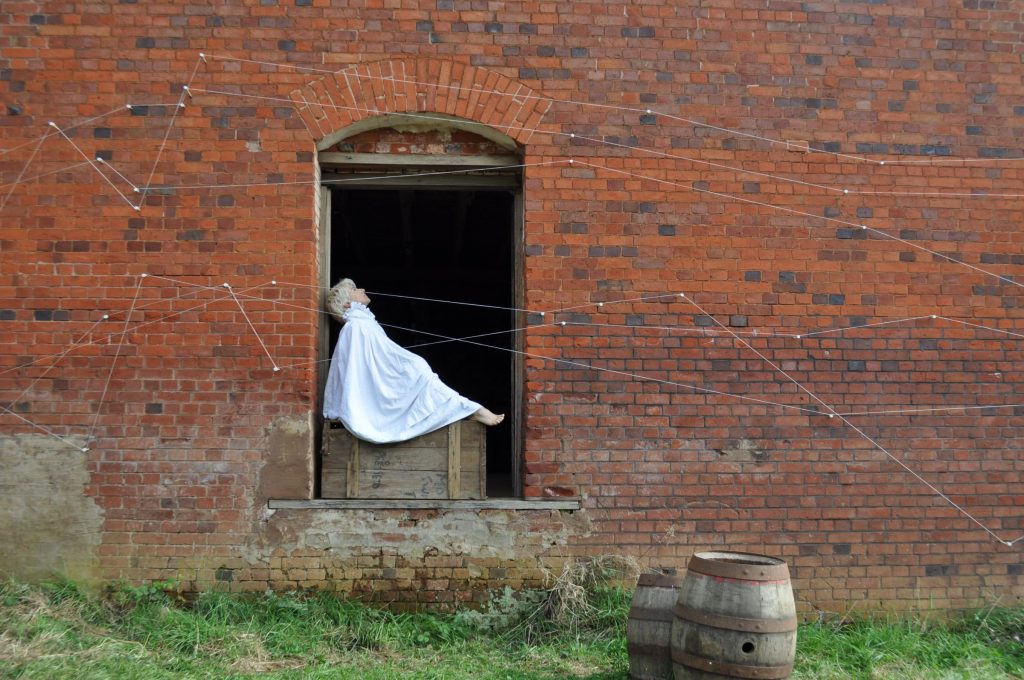

Site Geist II prioritises sustained close relationship with site by mapping imagined choreography onto walls of settler buildings using string and dowl. By looking for places of instigation from the wall ‘itself’, I was negotiating ever-changing encounters between constructed artefacts and materials. The insertion of dowl into extant crevices, avoiding imposition, engenders linework that dances over the wall. These ‘constellations’ of point and line to plane are ephemeral in both appearance and construction. The future step in this tactic is to draw choreography from the resulting lines. This way, the wall dances.’

Paul:

‘Our work in recent years has been about tracing links between our nervous systems and oppressive and not-oppressive culture (architecture, dress, music style). Both tactics offer a transdisciplinary reading of the Australian curatorial team’s theme Unsettling Queenstown project. Their interest in exploring narrative, temporality and relationality to yield correspondingly rich architectural manifestations has strong connections with our approach.

The dancer in these photos is Felicity Bott. The photopgrapher is Paul Wakelam. Their deeply cultivated respective artistries are integral to the processes and outputs and contribute indelibly to any impact the tactic might have.

Field Tactic paredarerme Swansea Farm Building

Field Tactic paredarerme Cranbrook Mill

2023 Biennale Architettura has seen Curator Lesley Lokko persistently lead with the question:

What does it mean to be ‘an agent of change’?

For us, change starts with the human nervous system – more specifically, our autonomic nervous system. We have found that to loosen up extant and entrenched ideologies within our cultural production we have first had to try to ‘decolonise’ our own nervous systems. Such is our imprinting as human animals, it hasn’t been easy:

What happens in vagus, stays in vagus (baby).

Consequently, theories about the human autonomic nervous system have informed our creative processes in recent years. The tactics we bring to the conversation being had at the 2023 Venice Architecture share something of what we have found.Being part of the Open Archive within the Australian Pavilion has enabled creative explorations that we commenced five years ago to find a deeper conversation. We are excited about this. That this conversation is driven by how architecture is connected to both ‘moment and process’ utterly fits with our ongoing preoccupation with how a….

‘state of becoming’

is required in all our acts of creative generation and regeneration, be it architecture or performance. Commitment to a ‘state of becoming’ draws us inexorably to a coalface whereat the integral relationship between vulnerability and risk is often painfully apparent.

The visual language and conceptual articulations of this tactic resonate strongly with the Biennale’s overall themes. Site Geist II offers a transdisciplinary reading of relationality as a tactic that potentially yields correspondingly rich architectural manifestations.

2023 Biennale Architettura Curator Lesley Lokko leads with the question what it means to be ‘agents of change’. For us, Paul Wakelam Architect and Felicity Bott of Great Southern Dance, change starts with the human nervous system. We have found that to loosen up extant and entrenched ideologies within our cultural production we have first had to try ‘decolonise’ our own nervous systems. And so, theories about the human autonomic nervous system have informed our creative processes in recent years.

We are excited that being part of the Open Archive within the Australian Pavilion has enabled creative explorations commenced five years ago to find a conversation. That this conversation is driven by how architecture is connected to both ‘moment and process’ utterly fits with our ongoing preoccupation with how a ‘state of becoming’ is required in all our acts of creative generation and regeneration, be it architecture or performance. Commitment to a ‘state of becoming’ draws us inexorably to a coalface whereat the integral relationship between vulnerability and risk is often painfully apparent.

We launch our architecture and dance from within DEEPROOM, a processed-based 30-year active ‘archive’. Our offering to the Biennale Architettura 2023 are the Site Geist I and Site Geist II tactics. These invite viewers to engage somatically and imaginatively with moving and still images of humans dancing within the ruins of the machinery colonisation.

We have been inspired by Nayyirah Waheed’s poetry, particularly _the release…

decolonization

requires

acknowledging

that your

needs and desires

should

never

come at the expense of another’s

life energy.

it is being honest

that

you have been spoiled

by a machine

that

is not feeding your freedom

but

feeding

you

The milk of pain.

__the release

nayyirah waheed

Another fundamental foundation for our work over the past five years is the Uluru Statement from the Heart. When we first encountered it in early 2018 we found the generosity of the statement was overwhelming. It had existential resonance for us. We had both turned 50 that year and considered the statement the single most important cultural event of our lifetimes. We felt fortunate to be alive at the juncture in history where such a statement had come into place. The statement offered vital definition to our place, our ‘home’ within ‘Australian’ human history. The statement spoke to our nervous systems, below the level of the brain stem, making our world feel more rational, more real – ‘safer’.

Significantly, the Uluru statement clearly indicated ‘sovereignty’ but did not wield it. It was an offer that sought not to dominate, but to move into step, to pull up alongside or indeed within existing structures to strengthen and synergise, mould and reshape them, to dismantle where needed without ripping down or away. It reminded us of the creative process and here is why:

The ‘state of becoming’ afforded by being inside a creative moment we experience as an ‘antidote to oppression.’

Felicity:

‘Is the idea of ‘safe space’ or ‘I didn’t feel safe’ another way of saying ‘it was oppressive’ ‘that is oppressive’ or, ‘the needs/demands of another’s nervous system or another ontological system are “sovereign” over mine in this moment’?

Paul:

‘Our work in recent years has been about tracing links between our nervous systems and oppressive and not-oppressive culture (architecture, dress, music style). Both tactics offer a transdisciplinary reading of the Australian curatorial team’s theme Unsettling Queenstown project. Their interest in exploring narrative, temporality and relationality to yield correspondingly rich architectural manifestations has strong connections with our approach.

The aperture through which to engage with this imagery in both tactics is your nervous system. Breathe deeply in and with a longer exhale, sit back and give over to the pace, the sounds and the attention of the dancers’ bodies to site/s. Watch with your gut, connect it with your heart and then head.

In April 2021, Professor Dorita Hannah posited the question ‘what is sovereign here?’ into our process. It continues to ring in my ears.

Site Geist I & II are parts of a larger investigation that faces troubled histories and uncertain futures and unsettles notions of settlement. By opening new terrains of performance and building, we’re asking what shared sovereignty – in the broadest sense; with landscape, bodies, constructed artefacts and multiple species – might look like.’

Curator of the 18th International Architecture Exhibition – Lesley Lokko

THE LABORATORY OF THE FUTURE

AGENTS OF CHANGE

What does it mean to be ‘an agent of change’? The question has shadowed the gestation period of The Laboratory of the Future, acting as both counterfoil and lifeforce to the exhibition as it has unfolded in the mind’s eye, where it now hovers, almost at the moment of its birth. Over the past nine months, in hundreds of conversations, text messages, Zoom calls and meetings, the question of whether exhibitions of this scale — both in terms of carbon and cost — are justified, has surfaced time and again. In May last year, I referred to the exhibition several times as ‘a story’, a narrative unfolding in space. Today, my understanding has changed. An architecture exhibition is both a moment and a process. It borrows its structure and format from art exhibitions, but it differs from art in critical ways which often go unnoticed. Aside from the desire to tell a story, questions of production, resources and representation are central to the way an architecture exhibition comes into the world, yet are rarely acknowledged or discussed. From the outset, it was clear that the essential gesture of The Laboratory of the Future would be ‘change’. In those same discussions that sought to justify the exhibition’s existence were difficult and often emotional conversations to do with resources, rights, and risk. For the first time ever, the spotlight has fallen on Africa and the African Diaspora, that fluid and enmeshed culture of people of African descent that now straddles the globe. What do we wish to say? How will what we say change anything? And, perhaps most importantly of all, how will what we say interact with and infuse what ‘others’ say, so that the exhibition is not a single story, but multiple stories that reflect the vexing, gorgeous kaleidoscope of ideas, contexts, aspirations, and meanings that is every voice responding to the issues of its time?

It is often said that culture is the sum total of the stories we tell ourselves, about ourselves. Whilst it is true, what is missing in the statement is any acknowledgement of who the ‘we’ in question is. In architecture particularly, the dominant voice has historically been a singular, exclusive voice, whose reach and power ignores huge swathes of humanity — financially, creatively, conceptually — as though we have been listening and speaking in one tongue only. The ‘story’ of architecture is therefore incomplete. Not wrong, but incomplete. It is in this context particularly that exhibitions matter. They are a unique moment in which to augment, change, or re-tell a story, whose audience and impact is felt far beyond the physical walls and spaces that hold it. What we say publicly matters because it is the ground on which change is built, in tiny increments as well as giant leaps.

Lesley Lokko